TCM meridians and fascia: what do they have to do with the internal arts?

This is a first for this blog, and I hope it’s not the last. Today I’m featuring a guest blogger, Trevor Aungthan. He is both a gifted student of multiple martial systems (internal and external) as well as a qualified and experienced physiotherapist who has worked with Cirque du Soleil and is the creator of an exciting new exercise program called "Circus Conditioning". In this article Trevor gives a fascinating and highly informative analysis of the meridians of traditional Chinese medicine, fascia and the internal arts. Enjoy!

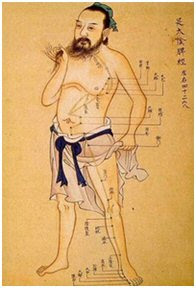

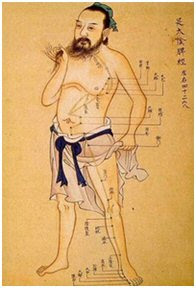

If you've ever seen an acupuncturist, you may have heard what Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) practitioners call 'meridians' - these are the pathways that Qi (or Chi) flow through in our bodies. There are 14 meridians and along each meridian are Qi (or acupuncture) points where Qi can be manipulated to restore balance, via acupuncture needles or acupoint pressure. Much research has been done and is currently ongoing on the correlation between TCM meridians and our own fascial pathways. The fascial pathways are interconnected lines of fascia, or connective tissue, that run in various trains throughout our body (see Anatomy Trains for more details). Tai Chi quan and other Internal Martial Arts (IMA) are believed to help cultivate our Qi as a dynamic, flowing form of Qi gong.

If you've ever seen an acupuncturist, you may have heard what Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) practitioners call 'meridians' - these are the pathways that Qi (or Chi) flow through in our bodies. There are 14 meridians and along each meridian are Qi (or acupuncture) points where Qi can be manipulated to restore balance, via acupuncture needles or acupoint pressure. Much research has been done and is currently ongoing on the correlation between TCM meridians and our own fascial pathways. The fascial pathways are interconnected lines of fascia, or connective tissue, that run in various trains throughout our body (see Anatomy Trains for more details). Tai Chi quan and other Internal Martial Arts (IMA) are believed to help cultivate our Qi as a dynamic, flowing form of Qi gong.

So what is the link between these systems: the meridians and the fascial network and how does it relate to IMA practice?

Have a look at the following picture of the Superficial Back Line (SBL) - which is an interconnected fascial chain - from Anatomy Trains (Myers, 2nd Ed. 2009) juxtaposed with the bladder meridian.

Pretty close right?

Similarly, the other six Anatomy Trains correlate very closely with the other meridians i.e. Superficial Front Line = Stomach meridian and the Lateral Line = Gall Bladder.

One of the pioneers in research into TCM meridians and fascia is Helene Langevin, a Professor in Neurology from the University of Vermont. Langevin and her team found that most of the Qi points occur where fascia planes or networks converge. They showed that acupuncture points mostly lie along the fascia planes between muscles or between a muscle and tendon or bone. When an acupuncture needle pierces the skin, it penetrates through the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, then through deeper interstitial connective tissue. Langevin hypothesized that a Qi blockage can be viewed as an alteration in the composition of the fascia and that needling or acupressure may bring about cellular change in the fascia (Langevin & Yandow, 2002).

We, probably more than anyone else, already use our fascial systems whenever we practice jibengong (foundational exercise) or via forms practice without many of us realizing it. At the base level, everytime we were told to fang song (relax) what was our laoshi or sifu really trying to tell us?

I know, personally, it was a difficult concept for me to comprehend - movement without muscular activation - or movement without a reliance on overt muscular activation.

If the muscles were not to work, how was I moving my body through space? How were my arms 'parting the horses mane' without my deltoids, pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi co-activating the movement required?

One word –

Fascia

Guimberteau

It was my fascial network all along that was driving the movement. Fascia has long been neglected as just the 'white packing stuff' around our muscles - anatomy labs around the world have been in competition as to who can clear out the fascia best so that the muscles are left pristine for examination and study. Looking at the video above by Dr Guimberteau which shows video of fascia in-vivo, in live fascial tissue, we can see the chaotic, fractal design of our fascial networks. In the last few years, there has been a paradigm shift in how we look at fascia and what it means for movement, health and dysfunction.

The traditional model of the human spine was based upon the post-and-beam model of a skyscraper (Schultz, 1983) and the soft tissues (muscles, fascia, tendons, etc) were always regarded as just curtain walls or stabilizing guy wires. If we assume our bodies as non-living organisms, this may hold weight but as biological structures we are mobile, flexible-hinged, low energy consuming, omni-directional structures that can function in a gravity-free environment (Levin, 1995). Skyscrapers are immobile, rigidly hinged, high energy consuming, vertically oriented structures that depend on gravity to hold them together. Similarly, the lever model we have previously used to explain muscles and joints in the body is flawed. See below.

A load of 200 kg, (not unusual for a trained weight lifter), located 40 cm from the fulcrum requires a muscle reaction force of 8 x 200 = 1600 kg. The erector spinae group can generate a force of about 200 to 400 kg, a force of only one quarter to one half of that necessary. Even a weight of 25 kg would put an average man at risk of tearing his back muscles. Muscle power alone cannot lift moderately heavy loads close to the body or light loads extending out from the body, such as a fish on the end of a rod. The calculated forces of these actions would rip muscles, break bones and severely deplete energy stores (Levin, 1995). The model nowadays agreed upon which most closely resembles our bodies' is based upon the tensegrity model, a type of truss system, which is omni-directional so that the tension elements always function in tension no matter the direction of applied force (Fuller, 1975).

A load of 200 kg, (not unusual for a trained weight lifter), located 40 cm from the fulcrum requires a muscle reaction force of 8 x 200 = 1600 kg. The erector spinae group can generate a force of about 200 to 400 kg, a force of only one quarter to one half of that necessary. Even a weight of 25 kg would put an average man at risk of tearing his back muscles. Muscle power alone cannot lift moderately heavy loads close to the body or light loads extending out from the body, such as a fish on the end of a rod. The calculated forces of these actions would rip muscles, break bones and severely deplete energy stores (Levin, 1995). The model nowadays agreed upon which most closely resembles our bodies' is based upon the tensegrity model, a type of truss system, which is omni-directional so that the tension elements always function in tension no matter the direction of applied force (Fuller, 1975).

A balloon is a great example of tensegrity; the skin of the balloon is the 'tension member' pulling in, the air is the 'compression member' pushing out; replace a series of rubber bands in lieu of the skin and dowels for the air in the balloon and you have a classic tensegrity structure (Myers, 2012). If we substitute bones for the dowels and our fascial and myofascial membranes for the rubber bands/skin, that is the fascial integrity of our body.

A balloon is a great example of tensegrity; the skin of the balloon is the 'tension member' pulling in, the air is the 'compression member' pushing out; replace a series of rubber bands in lieu of the skin and dowels for the air in the balloon and you have a classic tensegrity structure (Myers, 2012). If we substitute bones for the dowels and our fascial and myofascial membranes for the rubber bands/skin, that is the fascial integrity of our body.

If we take a look at the drawing of 'spiral Qi lines' by Chen Xin taken from his book, Illustrated Explanations of Chen Family Taijiquan, what seem like random circular drawings around the body were possibly an early attempt to explain the concept of fascial integrity with what was familiar to Chen at the time - spiral Qi.

If we take a look at the drawing of 'spiral Qi lines' by Chen Xin taken from his book, Illustrated Explanations of Chen Family Taijiquan, what seem like random circular drawings around the body were possibly an early attempt to explain the concept of fascial integrity with what was familiar to Chen at the time - spiral Qi.

Another way to look at his drawings are a rather accurate 'force-map' for the major fascial connections in the body. A small excerpt from his book reveals his deep knowledge;

Another way to look at his drawings are a rather accurate 'force-map' for the major fascial connections in the body. A small excerpt from his book reveals his deep knowledge;

So how do we as IMA practitioners, or more importantly, as human beings attain this Fascial Fitness? Müller and Schleip (2011) outline six guidelines to efficiently train our fascia.

(1) Preparatory counter-movement, or pre-stretch

Before performing any movement, there should be a slight pre-tensioning in the opposite direction. This is like drawing a bow to shoot an arrow, the pulling back action of the bow string is akin to the pre-tension on the fascia before movement i.e jumping, leaping. An example from the IMA is beng quan from xingyiquan: the loading into the rear foot pre-tensions the fascia in the lower leg which helps explode forward into the punch.

Hebei xingyi master, Dong Ziyi, performing beng quan

(2) The Ninja principle

Just as this sounds, this involves performing dynamic movements such as jumping, leaping and hopping as lightly, silently and smoothly as possible. Each movement should flow into the next and any extraneous and jerky movements should be avoided. The video of Swedish high-jumper Stefan Holm below is a perfect example, jumping around 1.70M (!) seemingly effortlessly. To IMA practitioners this should need no explanation - we should endeavour to do this each and every time we practice!

Stefan Holm

(3) Dynamic stretching

Two types: fast and slow. Contemporary research now suggests that fast, dynamic stretching is actually beneficial to the elastic architecture of the connective tissue when performed correctly (Decoster et al, 2005). Muscles and tissue should always be warm when performed and jerky and abrupt movements should be avoided. When combined with a preparatory countermovement, this type of stretching is found to be even more effective (Fukashiro et al, 2006). Rhythmical controlled bouncing at end range, when warm, is effective at this.

With slow dynamic stretching, the aim is to focus on engaging the longest possible myofascial chains (Myers, 2009) rather than isolated muscle groups. These should be multidirectional movements with slight changes in angle and direction i.e. sideways or spiral-type movements to have maximum effect on large areas of the myofascial web. An example of this might be performing a downward dog stretch with a right-to-left side emphasis, focusing on lengthening each posterior myofascial chain (i.e hamstring and calf) separately.

(4) Proprioceptive refinement

Current research indicates that the superfical fascial layers of the body are in fact more densely populated with mechanoreceptors than tissues situated more internally (Stecco et al, 2008). This goes away from the traditional thought that joints were the source of most of our proprioceptive capabilities - it is now believed that joints only provide joint feedback when at end of range movements and not during physiological motions (Lu et al, 1985).

Wu style taijiquan

To best stimulate fascia in this way, 'fascial refinement' training is recommended i.e. super-slow movements that may not be perceptible to an observer and also very quick macro-movements of the body. This concept will be familiar with IMA practitioners that do zhan zhuang training (standing post) or who perform their tai chi or other forms/partner work at super slow speeds as well as fast-form training.

(5) Hydration and renewal

The video at the beginning by Dr JC Guimberteau illustrates how important water and hydration is to our fascia. Our fascia is predominantly made up of both moving and bound water molecules that move in/out of fascial tissue like a sponge in the more stressed areas when stretching (Schleip & Klingler 2007). More fluid re-fills these areas when the stretch is released, coming from the surrounding tissue as well as the lymphatic and vascular networks - pain or dysfunction in areas is due to poor rehydration at neglected areas. With these types of specific exercises and through various therapies (myofascial, foam roller, etc) the aim is to refresh these neglected areas.

Interval training is also recommended over long, intense periods of exercise to allow adequate rehydration of the fascia.

(6) Sustainability

Fascial changes, unlike muscular adaptation, can take a long time and researchers advise 6 to 24 months before any significant changes may take place. This time-frame will not deter any serious IMA or yoga practitioner. Training needs to be persistent, regular and in small doses for collagen re-adaptation to occur.

By adapting some or all of the properties of Fascial Fitness into our existing training regime will certainly help towards us moving and feeling better. The evidence seems to acknowledge that TCM practices were very advanced considering they were developed approximately 2000 years ago. Many of today's top athletes have already incorporated these principles into their training and anecdotal evidence is promising. It's also interesting to note that the experts advise 6 to 24 months for these fascial changes to take effect, rather close to certain timelines to gaining some basic skills in the IMA. I’ll finish with a video of Yiquan master Wang Binkui which I believe portrays rather nicely the elasticity, fluidity and resilience we all strive for.

Wang Binkui Yiquan

Copyright © 2012 Trevor Aungthan

Further study

Chen X: Illustrated Explanations of Chen Family Taijiquan. Translated from Chinese by Jarek Szymanski; © J.Szymanski 1999-2002.

Decoster LC, Cleland J, Altieri C, Russell P (2005) “The effects of hamstring stretching on range of motion: a systematic literature review,” J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 35(6): 377-87.

Fukashiro S, Hay DC, Nagano A (2006) “Biomechanical behavior of muscle-tendon complex during dynamic human movements,” J Appl Biomech 22(2): 131-47.

Fuller RB: Synergetics. New York, McMillan Publishing Co, 1975, pp 372-420.

Guimberteau, JC: Strolling under the Skin DVD.

Langevin HM and JA Yandow: Relationship of acupuncture points to connective tissue planes. The Anatomical Record (New Anat.) 269:257–265, 2002.

Levin SM: Spine: State of the Art Reviews. Volume 9/Number 2, May 1995 ©Hanley and Belfus, Philadelphia. Editor, Thomas Dorman, MD.

Lu Y, Chen C, Kallakuri S, Patwardhan A, Cavanaugh JM (2005) “Neural response of cervical facet joint capsule to stretch: a study of whiplash pain mechanism,” Stapp Car Crash J 49: 49-65.

Müller DG and Schleip R (2011): Fascial Fitness: Fascia oriented training for bodywork and movement therapies. FF Yearbook.

Schleip R, Klingler W (2007) “Fascial strain hardening correlates with matrix hydration changes,” in: Findley TW, Schleip R (eds.) Fascia Research: Basic science and implications to conventional and complementary health care. Elsevier GmbH, Munich, p.51.

Schultz AB: Biomechanics of the spine. In Low back pain and industrial and social disablement. American Back Pain Association. Nelson L ed, Redesign, London, 1983.

Stecco C, Porzionato A, Lancerotto L, Stecco A, Macchi V, Day JA, De Caro R (2008) “Histological study of the deep fasciae of the limbs,” J Bodyw Mov Ther 12(3): 225-230.

If you've ever seen an acupuncturist, you may have heard what Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) practitioners call 'meridians' - these are the pathways that Qi (or Chi) flow through in our bodies. There are 14 meridians and along each meridian are Qi (or acupuncture) points where Qi can be manipulated to restore balance, via acupuncture needles or acupoint pressure. Much research has been done and is currently ongoing on the correlation between TCM meridians and our own fascial pathways. The fascial pathways are interconnected lines of fascia, or connective tissue, that run in various trains throughout our body (see Anatomy Trains for more details). Tai Chi quan and other Internal Martial Arts (IMA) are believed to help cultivate our Qi as a dynamic, flowing form of Qi gong.

If you've ever seen an acupuncturist, you may have heard what Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) practitioners call 'meridians' - these are the pathways that Qi (or Chi) flow through in our bodies. There are 14 meridians and along each meridian are Qi (or acupuncture) points where Qi can be manipulated to restore balance, via acupuncture needles or acupoint pressure. Much research has been done and is currently ongoing on the correlation between TCM meridians and our own fascial pathways. The fascial pathways are interconnected lines of fascia, or connective tissue, that run in various trains throughout our body (see Anatomy Trains for more details). Tai Chi quan and other Internal Martial Arts (IMA) are believed to help cultivate our Qi as a dynamic, flowing form of Qi gong. So what is the link between these systems: the meridians and the fascial network and how does it relate to IMA practice?

Have a look at the following picture of the Superficial Back Line (SBL) - which is an interconnected fascial chain - from Anatomy Trains (Myers, 2nd Ed. 2009) juxtaposed with the bladder meridian.

Pretty close right?

Similarly, the other six Anatomy Trains correlate very closely with the other meridians i.e. Superficial Front Line = Stomach meridian and the Lateral Line = Gall Bladder.

One of the pioneers in research into TCM meridians and fascia is Helene Langevin, a Professor in Neurology from the University of Vermont. Langevin and her team found that most of the Qi points occur where fascia planes or networks converge. They showed that acupuncture points mostly lie along the fascia planes between muscles or between a muscle and tendon or bone. When an acupuncture needle pierces the skin, it penetrates through the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, then through deeper interstitial connective tissue. Langevin hypothesized that a Qi blockage can be viewed as an alteration in the composition of the fascia and that needling or acupressure may bring about cellular change in the fascia (Langevin & Yandow, 2002).

- Sun Xi Kun performing Bagua Single palm change from his book "Genuine Transmission of Bagua Quan"

We, probably more than anyone else, already use our fascial systems whenever we practice jibengong (foundational exercise) or via forms practice without many of us realizing it. At the base level, everytime we were told to fang song (relax) what was our laoshi or sifu really trying to tell us?

I know, personally, it was a difficult concept for me to comprehend - movement without muscular activation - or movement without a reliance on overt muscular activation.

If the muscles were not to work, how was I moving my body through space? How were my arms 'parting the horses mane' without my deltoids, pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi co-activating the movement required?

One word –

Fascia

Guimberteau

It was my fascial network all along that was driving the movement. Fascia has long been neglected as just the 'white packing stuff' around our muscles - anatomy labs around the world have been in competition as to who can clear out the fascia best so that the muscles are left pristine for examination and study. Looking at the video above by Dr Guimberteau which shows video of fascia in-vivo, in live fascial tissue, we can see the chaotic, fractal design of our fascial networks. In the last few years, there has been a paradigm shift in how we look at fascia and what it means for movement, health and dysfunction.

The traditional model of the human spine was based upon the post-and-beam model of a skyscraper (Schultz, 1983) and the soft tissues (muscles, fascia, tendons, etc) were always regarded as just curtain walls or stabilizing guy wires. If we assume our bodies as non-living organisms, this may hold weight but as biological structures we are mobile, flexible-hinged, low energy consuming, omni-directional structures that can function in a gravity-free environment (Levin, 1995). Skyscrapers are immobile, rigidly hinged, high energy consuming, vertically oriented structures that depend on gravity to hold them together. Similarly, the lever model we have previously used to explain muscles and joints in the body is flawed. See below.

A load of 200 kg, (not unusual for a trained weight lifter), located 40 cm from the fulcrum requires a muscle reaction force of 8 x 200 = 1600 kg. The erector spinae group can generate a force of about 200 to 400 kg, a force of only one quarter to one half of that necessary. Even a weight of 25 kg would put an average man at risk of tearing his back muscles. Muscle power alone cannot lift moderately heavy loads close to the body or light loads extending out from the body, such as a fish on the end of a rod. The calculated forces of these actions would rip muscles, break bones and severely deplete energy stores (Levin, 1995). The model nowadays agreed upon which most closely resembles our bodies' is based upon the tensegrity model, a type of truss system, which is omni-directional so that the tension elements always function in tension no matter the direction of applied force (Fuller, 1975).

A load of 200 kg, (not unusual for a trained weight lifter), located 40 cm from the fulcrum requires a muscle reaction force of 8 x 200 = 1600 kg. The erector spinae group can generate a force of about 200 to 400 kg, a force of only one quarter to one half of that necessary. Even a weight of 25 kg would put an average man at risk of tearing his back muscles. Muscle power alone cannot lift moderately heavy loads close to the body or light loads extending out from the body, such as a fish on the end of a rod. The calculated forces of these actions would rip muscles, break bones and severely deplete energy stores (Levin, 1995). The model nowadays agreed upon which most closely resembles our bodies' is based upon the tensegrity model, a type of truss system, which is omni-directional so that the tension elements always function in tension no matter the direction of applied force (Fuller, 1975).  A balloon is a great example of tensegrity; the skin of the balloon is the 'tension member' pulling in, the air is the 'compression member' pushing out; replace a series of rubber bands in lieu of the skin and dowels for the air in the balloon and you have a classic tensegrity structure (Myers, 2012). If we substitute bones for the dowels and our fascial and myofascial membranes for the rubber bands/skin, that is the fascial integrity of our body.

A balloon is a great example of tensegrity; the skin of the balloon is the 'tension member' pulling in, the air is the 'compression member' pushing out; replace a series of rubber bands in lieu of the skin and dowels for the air in the balloon and you have a classic tensegrity structure (Myers, 2012). If we substitute bones for the dowels and our fascial and myofascial membranes for the rubber bands/skin, that is the fascial integrity of our body.  If we take a look at the drawing of 'spiral Qi lines' by Chen Xin taken from his book, Illustrated Explanations of Chen Family Taijiquan, what seem like random circular drawings around the body were possibly an early attempt to explain the concept of fascial integrity with what was familiar to Chen at the time - spiral Qi.

If we take a look at the drawing of 'spiral Qi lines' by Chen Xin taken from his book, Illustrated Explanations of Chen Family Taijiquan, what seem like random circular drawings around the body were possibly an early attempt to explain the concept of fascial integrity with what was familiar to Chen at the time - spiral Qi.  Another way to look at his drawings are a rather accurate 'force-map' for the major fascial connections in the body. A small excerpt from his book reveals his deep knowledge;

Another way to look at his drawings are a rather accurate 'force-map' for the major fascial connections in the body. A small excerpt from his book reveals his deep knowledge;Coiling power (Chan Jin) is all over the body. Putting it most simply, there is coiling inward (Li Chan) and coiling outward (Wai Chan), which both appear once (one) moves. There is one (kind of coiling) when left hand is in front and right hand is behind; (or when) right hand is in front and left hand is behind....once Qi of the hand moves to the back of the foot, then big toe simultaneously closes with the hand and only at this moment (one can) step firmly...It's amazing to think 100 years ago, Chen was already alluding to things we now know about integrated movement (connectivity of the big toe to the rest of the body) and kinetic awareness (left-right hand interplay). These things play a big part in the new sub-science of Fascial Fitness, or in other words, how to train our fascia to be resilient and elastic as to perform optimally and prevent injuries (Müller and Schleip, 2011).

So how do we as IMA practitioners, or more importantly, as human beings attain this Fascial Fitness? Müller and Schleip (2011) outline six guidelines to efficiently train our fascia.

(1) Preparatory counter-movement, or pre-stretch

Before performing any movement, there should be a slight pre-tensioning in the opposite direction. This is like drawing a bow to shoot an arrow, the pulling back action of the bow string is akin to the pre-tension on the fascia before movement i.e jumping, leaping. An example from the IMA is beng quan from xingyiquan: the loading into the rear foot pre-tensions the fascia in the lower leg which helps explode forward into the punch.

Hebei xingyi master, Dong Ziyi, performing beng quan

(2) The Ninja principle

Just as this sounds, this involves performing dynamic movements such as jumping, leaping and hopping as lightly, silently and smoothly as possible. Each movement should flow into the next and any extraneous and jerky movements should be avoided. The video of Swedish high-jumper Stefan Holm below is a perfect example, jumping around 1.70M (!) seemingly effortlessly. To IMA practitioners this should need no explanation - we should endeavour to do this each and every time we practice!

Stefan Holm

(3) Dynamic stretching

Two types: fast and slow. Contemporary research now suggests that fast, dynamic stretching is actually beneficial to the elastic architecture of the connective tissue when performed correctly (Decoster et al, 2005). Muscles and tissue should always be warm when performed and jerky and abrupt movements should be avoided. When combined with a preparatory countermovement, this type of stretching is found to be even more effective (Fukashiro et al, 2006). Rhythmical controlled bouncing at end range, when warm, is effective at this.

With slow dynamic stretching, the aim is to focus on engaging the longest possible myofascial chains (Myers, 2009) rather than isolated muscle groups. These should be multidirectional movements with slight changes in angle and direction i.e. sideways or spiral-type movements to have maximum effect on large areas of the myofascial web. An example of this might be performing a downward dog stretch with a right-to-left side emphasis, focusing on lengthening each posterior myofascial chain (i.e hamstring and calf) separately.

(4) Proprioceptive refinement

Current research indicates that the superfical fascial layers of the body are in fact more densely populated with mechanoreceptors than tissues situated more internally (Stecco et al, 2008). This goes away from the traditional thought that joints were the source of most of our proprioceptive capabilities - it is now believed that joints only provide joint feedback when at end of range movements and not during physiological motions (Lu et al, 1985).

Wu style taijiquan

To best stimulate fascia in this way, 'fascial refinement' training is recommended i.e. super-slow movements that may not be perceptible to an observer and also very quick macro-movements of the body. This concept will be familiar with IMA practitioners that do zhan zhuang training (standing post) or who perform their tai chi or other forms/partner work at super slow speeds as well as fast-form training.

(5) Hydration and renewal

The video at the beginning by Dr JC Guimberteau illustrates how important water and hydration is to our fascia. Our fascia is predominantly made up of both moving and bound water molecules that move in/out of fascial tissue like a sponge in the more stressed areas when stretching (Schleip & Klingler 2007). More fluid re-fills these areas when the stretch is released, coming from the surrounding tissue as well as the lymphatic and vascular networks - pain or dysfunction in areas is due to poor rehydration at neglected areas. With these types of specific exercises and through various therapies (myofascial, foam roller, etc) the aim is to refresh these neglected areas.

Interval training is also recommended over long, intense periods of exercise to allow adequate rehydration of the fascia.

(6) Sustainability

Fascial changes, unlike muscular adaptation, can take a long time and researchers advise 6 to 24 months before any significant changes may take place. This time-frame will not deter any serious IMA or yoga practitioner. Training needs to be persistent, regular and in small doses for collagen re-adaptation to occur.

By adapting some or all of the properties of Fascial Fitness into our existing training regime will certainly help towards us moving and feeling better. The evidence seems to acknowledge that TCM practices were very advanced considering they were developed approximately 2000 years ago. Many of today's top athletes have already incorporated these principles into their training and anecdotal evidence is promising. It's also interesting to note that the experts advise 6 to 24 months for these fascial changes to take effect, rather close to certain timelines to gaining some basic skills in the IMA. I’ll finish with a video of Yiquan master Wang Binkui which I believe portrays rather nicely the elasticity, fluidity and resilience we all strive for.

Wang Binkui Yiquan

Copyright © 2012 Trevor Aungthan

Further study

Chen X: Illustrated Explanations of Chen Family Taijiquan. Translated from Chinese by Jarek Szymanski; © J.Szymanski 1999-2002.

Decoster LC, Cleland J, Altieri C, Russell P (2005) “The effects of hamstring stretching on range of motion: a systematic literature review,” J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 35(6): 377-87.

Fukashiro S, Hay DC, Nagano A (2006) “Biomechanical behavior of muscle-tendon complex during dynamic human movements,” J Appl Biomech 22(2): 131-47.

Fuller RB: Synergetics. New York, McMillan Publishing Co, 1975, pp 372-420.

Guimberteau, JC: Strolling under the Skin DVD.

Langevin HM and JA Yandow: Relationship of acupuncture points to connective tissue planes. The Anatomical Record (New Anat.) 269:257–265, 2002.

Levin SM: Spine: State of the Art Reviews. Volume 9/Number 2, May 1995 ©Hanley and Belfus, Philadelphia. Editor, Thomas Dorman, MD.

Lu Y, Chen C, Kallakuri S, Patwardhan A, Cavanaugh JM (2005) “Neural response of cervical facet joint capsule to stretch: a study of whiplash pain mechanism,” Stapp Car Crash J 49: 49-65.

Müller DG and Schleip R (2011): Fascial Fitness: Fascia oriented training for bodywork and movement therapies. FF Yearbook.

Schleip R, Klingler W (2007) “Fascial strain hardening correlates with matrix hydration changes,” in: Findley TW, Schleip R (eds.) Fascia Research: Basic science and implications to conventional and complementary health care. Elsevier GmbH, Munich, p.51.

Schultz AB: Biomechanics of the spine. In Low back pain and industrial and social disablement. American Back Pain Association. Nelson L ed, Redesign, London, 1983.

Stecco C, Porzionato A, Lancerotto L, Stecco A, Macchi V, Day JA, De Caro R (2008) “Histological study of the deep fasciae of the limbs,” J Bodyw Mov Ther 12(3): 225-230.

Brilliant stuff...glad for this post, as I never heard of it.

ReplyDeleteI know this blog deals with Eastern arts, but, pulling it back to my own frame of reference: a lot of this stuff applies to capoeira, as well (inevitably): its emphasis on fluidity; the dynamic shifts between fast and slow movements; and capoeira's basic movement itself--the ginga, a swinging, shifting stance that sounds like "preparatory counter movement" in action.

On another note, "rhythmical controlled bouncing" makes me think of the great baseball pitcher Satchel Page's advice to "Keep the juices flowing by jangling around gently as you move."

Again, great post.

This was an extremely interesting post. I've downloaded a copy of it for personal reference as I'm sure I'll want to refer to it in the future. Great work, keep em coming!

ReplyDeleteThanks for the comments guys.

ReplyDelete@Patch - yes, Caporeira certainly has those elements, especially the angola style if i'm not mistaken? Watching the ginga and having done it myself I would agree it is an excellent form of prep counter-movement. Nice observation!

@Ryan - That's great to hear. I've got some other interesting articles in mind - i'll just have to convince Dan to let me guest-post again! : )

You won't have to twist my arm very hard Trev!

DeleteGreat article Trev!

ReplyDeleteHearing Dr. Yang's lecture on how fascia, that layers with fat and muscles in the abdomen, forms a battery that stores chi and operates also as a fountain of youth site, was the first time I started to accurately juxtapose fascia with the human kinetic system.

ReplyDeleteIf the rest of the body have this, even if in thin layers, then it was even more important to study the conductive or resistive properties of such, because so far nerves and bone transmit or produce electricity. And if the fascia is another way for this electricity to be moved around the body like an electrical circuit board using resistors, then the human body has now become a very complicated electrical circuit imposed within an EM field much like an EMP bomb affecting an electronic board of circuits.

Due to the body's natural resistance value, however, external and internal sensors have yet to be able to find the "poles" of the body because as everyone knows in electrical engineering, you don't get the right values unless you connect the positive and negative to the right point and the right ground. There's no way simply connecting a voltage analyzer to the outside of the body will detect any of this energy. So because Western science cannot see or detect it, it has become a "field effect". Meaning, something that you can only see in the fields because of the wind moving the plants around, but you cannot see the wind. Thus electromagnetic fields were said to be a "field effect".

Well, even if that wasn't the case, it is the case now.

Thanks Nen!

ReplyDeleteVery interesting comments you make Ymar, thanks for reading.

Trevor,

ReplyDeleteExcellent article! I am making this required reading for all of my students. The discussion on the tensegrity model was particularly interesting. Looking forward to more.

Many of the old karate masters figured this out as well, in part due to the focus on harnessing power in the core abdomen. That is why old masters often said the same thing : power comes from the stomach or hara. They didn't have PhDs or scientific experiments to back this up. They just had their eyes that saw the consequences of the wind moving things. Of course real scientists in the past, pioneers and not just deskmonkey jockeys, had to use their eyes as well since the instruments to detect the undetectable, did not exist. And would not exist without those pioneers.

ReplyDeleteTrevor, keep up your research. Humanity has great need of this progress, since human mortality and vices encompass this entire planet.

In the ancient world, this knowledge would have been used to preserve life by killing enemies. In the modern world, we have bombs and nukes for killing, but only Western medical monopolies and politics for the life preservation part. It has gotten a little too top heavy and needs a correction.

It has never been the case that when humanity could benefit from new knowledge and wisdom, that the majority of humans accepted the new thing easily. Same thing with carriers when they replaced battleships in WWII. If humanity could so easily improve our methods, we wouldn't geniuses, pioneers, and autodidacts to uplift the masses.

Due to discussions with Sanko over at his blog concerning the progress of students through beginner, proficiency, and the road to mastery, I decided to compile some of my sources on Chinese martial history to back my statement that there is a more natural or efficient training methodology than has been accepted for modern martial arts or traditional martial arts.

ReplyDeleteIn your article, Trevor, you mentioned that it was somewhat surprising that Chinese T Medicine became so advanced even though it is 2000 years old (medical chi gong is actually around 4000 or more years old). That is something I took note of as well when I researched the matter from a more practical/martial stand point.

The simple and relevant fact is that they were able to research and develop things so highly because they used live experimentation: real life and death matches and tests. This is comparable to live human experimentation during WWII, often considered unethical yet the results are often much faster than comparative animal testing. The test simulated situation is closer to the target population (humans), and thus the results are more "efficient".

The human testing I am speaking of, is of course war, not mad scientists going wild. 2000+ years of it in fact, if not more. With family legacies using ancient scrolls and oral lessons to transmit and maintain that knowledge. Much has been lost due to political purges (Mao) and wars, but much has been preserved as well. When looking at what the Ancient Greeks and Ancient Chinese developed, it is quite easy to imagine how an European barbarian looked upon the ruins of the Ancients and believed that the Ancients had magic. In a fashion, they did. Any highly advanced technological level is imperceivable from magic.

In a military context, no matter how good an army looks an paper, such as China's 1 million man army, such things are meaningless absent real life experience and testing. This is why often the readiness reports and maintenance reports for US fighter craft, fixed rotary helicopters, and Army divisions were basically made up more or less during peacetime. This was the planet's supreme number 1 fighting force even. This was found out in Iraq in 2003. Stats on paper were designed to look good and were fluffed up. When it came to real life tests, the failures showed up pretty fast. And this always happens whenever you get new blood, which was 20 years in the Roman legion and 4-10 years in the US military. Which is about right when one considers the time period of the Gulf War. After each cycle, there must be a real life test, otherwise the entire system degrades and people eat up pie in the sky plans as if they were real food. It's just a mirage. And a lot of people end up dying in war precisely because the politicians and generals thought that the plans that looked so good on paper, would work just as good in reality.

China was never given an option to log out of reality in the past. Their development was forcibly sustained, and as a result, we saw what those ancestors achieved.

The time period for fascia and muscle elongation is very interesting in terms of shock type transfer movement utilizing kinetic chaining of muscles. Longer muscles, less inefficiency due to mechanical friction. This might very well explain the difference between my hand skills and those of my peers, given how I steadily improved them over 5-10 years. Yet my leg skills were never developed to that level, and so I find that there are certain energy losses that happen when I utilize Taiji movement. The movements are never as smooth as what I feel in my arms. Slow but steady. Don't burn yourself out as many external martial artists do.

Collating some practical training methods from some high level practitioners of the martial arts and my own experimentation, the ideal cycle for repetition drilling is essentially:

ReplyDelete10% speed, sustained, throughout the movement.

50% speed, somewhat sustained and smooth, to link the mind to the body, idea to target. (This depends on one's mental concentration aspect. People with a lot of mental concentration can treat 10% speed as 50% speed, but most beginners have the mind or body "lagging" at that speed. They need to be synched up.)

100% speed to lock in all aspects together in one package.

These are then cycled again in threes. Physical conditioning may be done by cycling 3-10 fast ones, then 1-3 slow ones.

This was the training method I sought to achieve for myself ever since I learned of TFT's training methodology after 2001-3. Coincidentally, it also happens to be similar to the training methods martial artists that I consider "on the road to mastery" have also figured out for themselves.

As for "why" it works, there are theories. But nobody has spent much time on it, as far as I know, because it does work and that's all that really matters for people training self defense or battlefield application skills in the martial arts.

@Jose - thanks for sharing, glad you and your students can take something away from it.

ReplyDelete@Ymar - that's a very well written and interesting comment. Lot's of food for thought in there. Again, thanks for reading and following.

Trev

Trevor, glad you found them interesting or useful.

ReplyDeleteI actually read your article upside down, because I'm often times an unconventional thinker. I also read it in parts. I read the last part first. That's the gap you see in the comments. Then I read the middle. Now lastly, I read the first part.

My definition of relaxation, due to the fact that many people use it but semantically it means whatever people think it means which becomes a barrier in teacher-student relationships, is this.

Move only the muscles that need to be activated to do work, and turn off all muscles that are unnecessary for the work in question. This requires fine muscular control an order or more difficulty higher than simply the various fine motor control "techniques" seen in TMA. This is full body control, full creative expression, via a technical foundation. Imagine a person that can stop their heart and remain underwater, meditating, for an hour or so. Now imagine that same level of control over the body's gears, wheels, engine, fuel consumption, CPU, and RAM access speed. The human mind becomes the weapon, a CPU fitted inside a massive world killer strategic fortress. In order for students to learn how to turn off muscles, they should utilize feeling, since that's how chi and nerves connect their own muscles together anyways, to their CPU or brain. That means touching their specific muscles to tell them where to focus and to ask them to touch your own muscle activation cycles for them to visualize the process better. All things that Chinese martial arts more or less ended up utilizing as a training methodology. A core difference between them and the rest of the world. The Japanese do not do this. The closest they got was slapping a stick on your leg if your posture was wrong. That was more of a pain compliance issue though.

Two additional points I wanted to make after reading the first few paragraphs of your article, which I did just now in fact. Morticians and criminal forensic doctors dissect and clean corpses. One of the methods they use is an internal suction machine that takes all the fluids and I assume fascia as well, churn it into an output that ends up in the bio mess compactor or trash. That's what they do with it. The morticians definitely don't study it for any forensic purposes. It's not on the Western medical radar so to speak.

Which is an implication that there is a major sensory hole in Western medicine and thought. But since we're dealing with humans, that is never as surprising as people might assume.

The second point I wanted to make is that high level athletes have already figured out the slow/fast cycle through experimentation. It just works. But we associate athleticism with slimness, rock hard six pack abs, and so forth. But I've seen several internal MA users that were pretty fat around the belly there. One wonders exactly how the power generation and furnace is working in that body structure. Western medicine has turned a rather blind eye to this issue, and it is still blind to the causes of obesity. I've also seen people who utilize Matt Furey's body weight conditioning. Their muscles are rather fatty (viscous). That is the look of "functional muscles". Weight trained muscles are actually risky and dangerous even though they look "good", and not just because of Bruce Lee's own eventually fatal accident weight training. This "fatty" type muscle lets them generate huge amounts of power and endurance, however. It was an interesting thing I just connected to now. Maybe in these circumstances, it wasn't "fat" but "fascia" that was involved.

In addition to Anatomy Trains, consider reviewing (Frederick & Frederick, Human Kinetics, 2006). The authors combined the facial theory of Anatomy Trains with their backgrounds in movement, physical therapy, and martial arts, and formulated a broad, practical stretch program for athletes. Their approach has been adopted by many top athletes in the NFL and MLB.

ReplyDelete